The Water Before Us: Everything Affects Everything

A beautiful postcard sent from rural Tennessee to the world: here's what possible when we work together.

Food as a verb thanks

for sponsoring this series

A story of water, community and survival.

This is the first in a multi-story collaboration with Thrive Regional Partnership.

The "Before Us" series examines our shared connection to the region's landscapes and spotlights the people preserving them for generations to come.

*******

The Laurel Dace is a species of minnow - stretching two inches perhaps, like a gherkin pickle - with a gorgeous gold stripe running horizontal across its midline like a bright equator with more yellow on its fins, as if partially dipped in gold.

It has big, Mr. Magoo-eyes and bright red lips, like the fish is wearing Revlon.

During mating season, the males - their bellies turning bright red with desire - swim up and down and around the females in a choose-me dance.

The Laurel Dace feeds on insects - caddisflies, mayflies, stoneflies, damselflies - and spawns multiple times each spring, laying dozens of eggs in the hidden spaces under and between rocks at the bottom of creek beds and streams.

It is also perilously close to extinction.

Its numbers so low, you can count them by hand.

The Laurel Dace is considered one of the most critically endangered fish in the US.

Scientists estimate there are perhaps 800 Laurel Dace left on Earth.

They're found in only one place on the planet.

Walden's Ridge, Tennessee.

"This is the last stream on planet Earth where you can reliably find Laurel Dace," said Dr. Bernie Kuhajda, aquatic conservation biologist with the Tennessee Aquarium.

We are standing in Bumbee Creek on Walden's Ridge, above Spring City, Tenn., at the end of a series of long roads - asphalt, gravel, dirt, rocks, ruts - on private land with a locked gate.

With us: Bernie and his team of scientists from the Tennessee Aquarium's Conservation Institute (TNACI).

They're in a race against time and human behavior to save the Laurel Dace from extinction.

There in Bumbee Creek, they toss seine nets into the knee-deep water, looking - hope, fear, all mixed together - for the small fish.

They find one.

"A female!" Bernie declares.

The fish is already small; its vulnerability makes it seem even smaller. The moment is surreal and dizzying with both exhilaration and grief, witnessing a creature whose population is so limited, the loss of even one is noted as tragic.

"Isn't she beautiful?" Bernie says.

Once upon a time, the Laurel Dace flourished in nine nearby streams. In the 90s, Bernie remembers driving by Soddy Creek, hopping out with a seine net and catching them hand-over-fist.

Now?

"They are completely gone," he said.

The Laurel Dace is threatened by several forces, from invasive species like bass and sunfish to haphazard land management practices that flood its habitat. Most of the threat can be summed up in one word:

"Sedimentation," Bernie said.

Sedimentation ruins and chokes out the Laurel Dace habitat.

Yet, sedimentation also impacts and damages human habitats - our economies, homes, businesses - as well.

Sedimentation is caused by humans and can be prevented by humans.

The Laurel Dace story portrays a boomerang effect: what befalls the Laurel Dace also befalls us.

Its story, parallel to ours.

"What the Laurel Dace is going through is exactly what we're going through," said Stephania Motes, Spring City's former city manager.

The Water Before Us is the first in a multi-part series examining the crucial role of larger landscapes within our region. In a special collaboration with Thrive Regional Partnership, Food as a Verb is expanding our coverage with a question:

What is the health of the watersheds and forests in the background beyond our farms and fields?

And what are the opportunities before us for healing?

In the race to save the little Laurel Dace, a precious and rare truth is discovered.

When the fish thrives, so do we.

Decades ago in college, Bernie signed up for vertebrate zoology; the professor, an ichthyologist, took field trips to a stream near campus. Bernie had driven by the stream dozens of times, never giving it a second glance.

But that undergraduate day, as he waded into the stream, a whole new world opened up, this underwater kingdom hidden in plain sight.

"All this amazing diversity hidden under the surface of the water," he said.

"I got hooked."

Degree after degree, publication after publication, Bernie built his career on conservation and freshwater fish.

"Freshwater covers less than one percent of the world," he said, "but about half of all species of fish are freshwater."

Here in the Southeast, particularly where Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia converge, we have a particular treasure:

"We have an underwater rainforest right here in the South," he said. "We are a global hotspot for freshwater diversity."

Thus, joy.

And vulnerability.

Within this rainforest-hotspot, there is tremendous interconnectivity. What happens in our fields impacts our streams, our towns, even - via the cavernous ground under our feet - our drinking water.

If you were to dye test water poured out in one field, you'd see it flowing to a thousand other places.

Everything affects everything. To understand all the interrelated parts, Bernie offers a Laurel Dace 101 crash course.

Remember its bulging eyes?

"They are sight feeders," Bernie said.

Standing on the Bumbee Creek rocks, he dips his boot in the water, and swirls it around. Immediately, mushrooms of dirt cloud the water.

"When the water looks like this, you're going to have trouble seeing aquatic insects to eat," he said.

Sedimentation fills in the spaces like chimney soot, dirtying clean gravel needed for spawning, clouding streams so fish can't find food and potentially decreasing oxygen levels.

Why the increased sedimentation?

Atop Walden's Ridge, hundreds of feet above Spring City, there are acres and acres of clear-cut.

In its natural state, the land boasts a built-in ability to absorb and contain rainfall, even torrential, like a natural buffer, so downstream watersheds aren't overwhelmed.

When practiced improperly, clear-cutting rips out the land's natural resiliency to hold water; when it rains, the land - stripped of its buffering ability - becomes like a race track, as rainfall floods into lower elevations.

This is why cities, historically, are more flood-prone than rural; all the impervious surfaces - parking lots, roads, asphalt - can't hold water, so runoff becomes fast and furious.

Clear-cutting replicates the urban in the rural. All the natural habitat is flattened, becoming a superhighway for rainwater runoff.

Logging roads must be cut; their ruts creating even more superhighways for overflow rainfall to rush into lower elevations.

Like Bumbee Creek.

And Spring City.

In the winter of 2019, the Piney River flooded its banks, causing massive destruction to Spring City businesses and families.

"It flooded roughly five city blocks in about five to 10 minutes," said Stephania Motes. (She's the former city manager; her two contributed photos follow.)

Downtown businesses took years to recover; some never did.

It was a wake-up call. In 2022, Spring City joined Thrive Regional Partnership's pilot Resilient Communities program, particularly for one reason:

"Flood mitigation," said Stephania.

Thrive and Spring City leaders hosted town halls and meetings around two central questions:

What is causing our flooding? Where are the solutions?

In one Resilient Communities meeting, Joel Houser with Open Space Institute mentioned the Laurel Dace: the rare, endangered fish only found nearby.

Stephania and former mayor Woody Evans stopped, with turned heads: say that again.

"We'd never heard of this before," she said.

The precious connection was made: that little fish is suffering in similar ways as Spring City residents.

"The sediment causing issues in the Laurel Dace's natural habitat was also causing flooding issues here," Stephania said.

Here, the Laurel Dace story becomes a beautiful postcard sent from rural Tennessee to the world: here's what possible when we work together.

Spring City suffered from flooding.

And the Laurel Dace suffered from over-sedimentation in its streams.

Both events are tied together.

Addressing one means addressing the other.

In doing so, something beautiful forms.

Community.

The Resilient Community process allowed neighbors, city leaders, land managers and business owners to meet together in conversation framed around solutions, not confrontation.

Stephania remembers land managers and business owners eager to learn about best practices.

"They actually wanted to start meeting with us," she said. "It really did open up a lot of doors."

Plus, Spring City leaders also saw opportunity.

"How special is it to find something in your own backyard that's nowhere else in the world?" she said.

Spring City began to embrace the Laurel Dace, which became the town's official fish. City leaders proclaimed May 17, 2025, as Laurel Dace Day. A downtown party, farmers' market, a 5k with more than 150 runners from as far away as Minneapolis and Washington State.

"We had runners from 36 different cities here," she said.

The embrace of the Laurel Dace has begun to transform Spring City: the tiniest, most vulnerable fish now linked to a city's identity.

"People's actions have consequences," Stephania said. "It may not be immediately in their backyard, but it does have consequences elsewhere."

Then, more help, more community.

In 2022, National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) partnered with the Aquarium on a multi-year project called Ridges to Rivers Regional Conservation Partnership Program.

The Ridges to Rivers project directly helps with on-ground training and financial support for regional farmers and land managers interested in shifting towards more regenerative or sustainable practices.

Clear-cutting will continue - wood, a renewable resource, will remain in demand - but best practices can reduce run-off damage downstream.

Local land managers are beginning to plant native grasslands post-cut, for example.

Farmers steeped in conventional practices often graze cattle near - and even into - streams and waterways, which reduces and even eliminates any riparian buffer between fields and waterways.

This leads to flooding which leads to sedimentation.

The shift? Rotational grazing and a fenced-off barrier between fields and waterways, which reduce run-off and downstream sedimentation.

Crop farmers who cover their rows with plastic for weed suppression often create super-waterslide conditions; when it rains, the water races over the plastic, often carrying pesticidal residue, downstream.

Sedimentation? Yes. Flooding? Yes.

The shift: planting live mulches and cover crops between rows reduces run-off, thus reducing sedimentation and flooding.

Yet, scientists and conservationists harbor one secret thought:

Will it be enough?

In 2024, the Laurel Dace faced an extinction-level event: the summer drought.

That summer, Bernie and his team went to check on the fish. Hiking through Bumbee Creek, they found: the water in the creek had nearly vanished.

"Bone dry," said Bernie.

The Laurel Dace were nearly all gone.

*******

TO Smith doesn't mince words. The former chief for Montana's Fish, Wildlife and Parks who also led conservation efforts in Texas, California and with Trout Unlimited - says two things about as plainly as possibly.

First: we live in a gem of a place.

"The lower Appalachia area around Chattanooga down towards Huntsville is the most biologically diverse area in North America," he said.

Second?

It's in dire trouble.

Particularly, our watersheds.

"Water is the biggest issue we have. Water and the sheer development. Development is fracturing the landscape and our water quality is under threat," he said.

"Water is the issue. Food comes after water. How are you going to do regenerative farming when you have a jacked-up watershed?"

Today, TO is the Director of Conservation for Southeastern Cave Conservancy and is quite adept at describing the cave wonderland underneath our feet: a porous geology of dissolving limestone that's best pictured not as solid rock, but a cavernous, Swiss Cheese underground.

"This is what is so special about where we live," he said. "It's karst."

This geological reality - a karst reality - affects everything downstream, including our drinking water.

In some places - Florida, California - rain falls and seeps into the ground, which holds, percolates and filters the water.

Not here.

"Like capillaries, like veins," TO said. "This whole area is like Sponge Bob Squarepants. That's what's under our feet.

"There's millions and millions and millions of tubes that range in size from the size of your hair up to as large as Mammoth Caverns. And they're everywhere."

When it rains, water seeps into those millions of hair-to-mammoth-sized highways, all bound for our watersheds.

Pour something on the ground, it's coming out in our water.

"It's on the A-Train," said TO. "It's going to run through a cave and under your feet and out into a spring and into the Tennessee River on its way to your drinking supply."

The Laurel Dace-Spring City tale is a looking glass into the larger story.

Spring City's embrace of the Laurel Dace is a microcosm for how communities and conservation can work together - trout streams in the West, forests in the Northeast - to solve intimately local problems.

TO spoke about Thrive and the quest for regional partnerships.

"If they are strategic about finding common threads, they can build a fabric through which a team of horses can solve some major problems," he said.

Less helpful practices are swapped for better ones.

Tiny fish benefit.

Farms benefit.

Downtowns and neighborhoods benefit.

Everything affects everything, and our actions have consequences. When the ecological truth of this - what goes into the ground there affects us here - becomes a political and cultural truth, things will shift.

Until then?

"It's like watching a horrible, horrible car accident and you can't do anything about it," said TO.

"You want to save those people. Stop the car! Don't turn left! You can see what can be done to prevent it, but it's up to them, not you."

Ten years ago, TNACI scientists went to Cupp Creek, also on Walden's Ridge, where Laurel Dace were known to be present.

With electroshock backpacks, they surveyed the water. They, too, were shocked.

"We counted 200 sunfishes and bass and we only found a single Laurel Dace," said Bernie. Three years later, the sunfish and bass population had tripled.

And the Laurel Dace were gone in Cupp Creek.

Invasive, the sunfish and bass escape from landowner ponds during flooding events, somehow making their way to streams and creeks, where vulnerable Laurel Dace have no defense.

"They have literally eaten all the minnows in Cupp Creek," said Bernie. "There are none left."

Then, last summer's drought.

TNACI scientists raced up to Walden's Ridge to search for Laurel Dace.

They found a few pockets, the scantest of puddles, raccoon tracks nearby. There, they found Laurel Dace huddling for survival.

In a moment of Noah's Ark urgency, they began scooping up and safeguarding the remaining Laurel Dace, transporting them back to TNACI's campus at The Baylor School.

They rescued 299 Laurel Dace.

One died during transport, leaving 298.

At TNACI, they began a heroic attempt at keeping a single species of fish preserved, alive and future-forward.

They filled tank after tank, with back-up generators and close-eye attention.

"We had all the Laurel Dace in the world here," said Bernie.

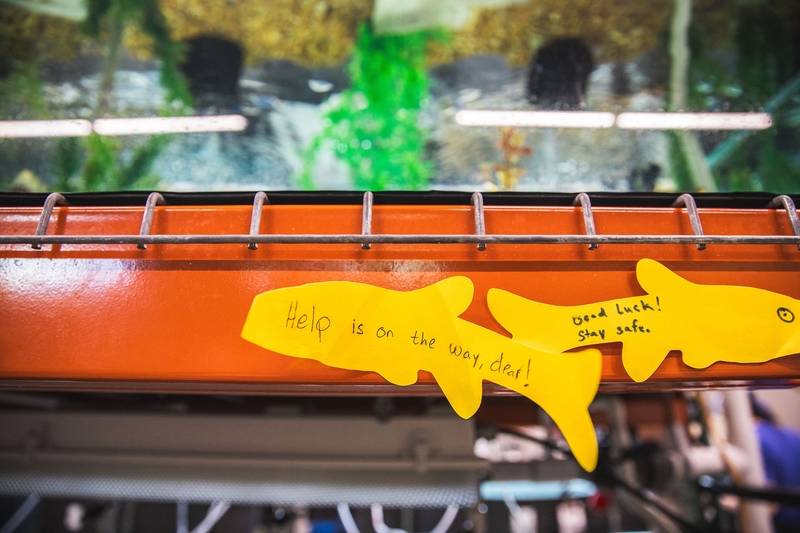

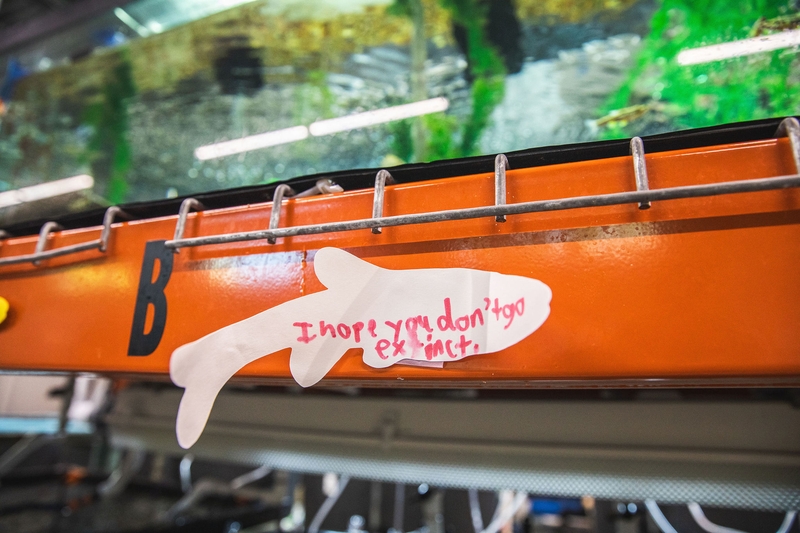

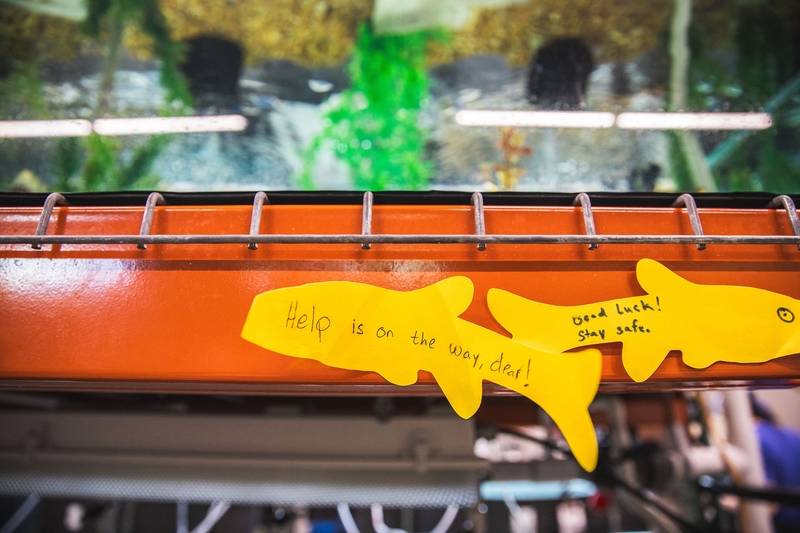

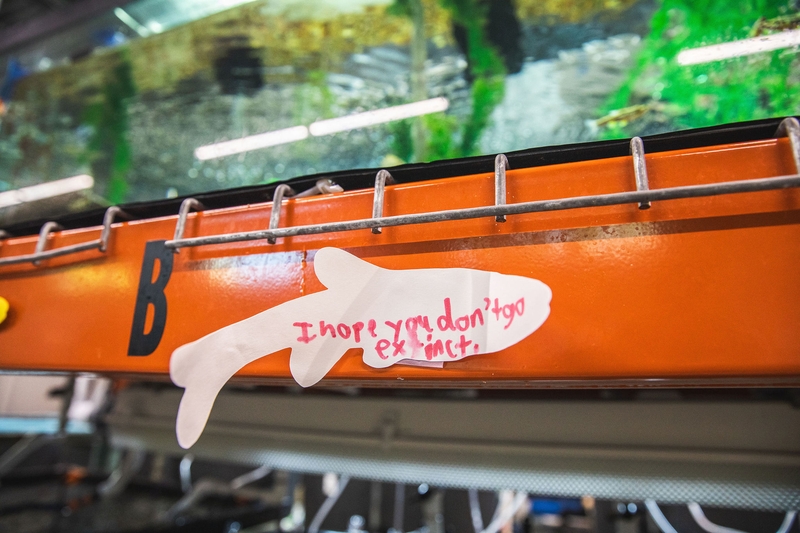

School kids visited, wrote notes.

Earlier this summer, Noah's Ark got bigger.

The Laurel Dace began spawning in TNACI tanks.

Now, baby Laurel Dace - the size of a grain of rice - number around 200 more.

Best estimate for all the living Laurel Dace?

"My best guess?" Bernie said. "Probably 800 to 900."

They've already released some back into Bumbee Creek. Days ago, they returned - hope, fear all mixed together - to survey their numbers.

They found one.

Then, another.

There were multiple juvenile Laurel Dace.

They'd spawned.

TNACI will always keep some Laurel Dace in its tanks, an Ark-ian insurance plan against a world that seems to tilt one way or the other:

Will we adopt new practices that protect and strengthen our communities, watersheds and natural habitats?

Will this tiny fish, facing peril at every turn, survive?

"Yes," Bernie said. "I am an eternal optimist. You have to be if your whole career is working with endangered species."

Behind him, swimming in tanks with back-up generators, hundreds of Laurel Dace, yellow running across their fins and midline, as if dipped in gold.

As if dipped in hope.

"Word will spread," he said. "I think we will turn it around."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.

For more information:

- Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (TNACI) "furthers the Aquarium’s impact by conducting scientific studies, restoring our region’s natural ecosystems and educating members of the public to take conservation action."

- Thrive Regional Partnership serves as a framework, connecting people to place in a wide network of relationships to inspire responsible growth in northeast Alabama, northwest Georgia and southeast Tennessee.

- Thrive's Natural Treasures Alliance is a collective of organizations working to accelerate landscape conservation to ensure a place that lasts for future generations.

- Southeastern Cave Conservancy is the world's largest land conservancy solely dedicated to protecting caves.

food as a verb thanks our sustaining partner:

food as a verb thanks our story sponsor:

Reflection Riding

A story of water, community and survival.

This is the first in a multi-story collaboration with Thrive Regional Partnership.

The "Before Us" series examines our shared connection to the region's landscapes and spotlights the people preserving them for generations to come.

*******

The Laurel Dace is a species of minnow - stretching two inches perhaps, like a gherkin pickle - with a gorgeous gold stripe running horizontal across its midline like a bright equator with more yellow on its fins, as if partially dipped in gold.

It has big, Mr. Magoo-eyes and bright red lips, like the fish is wearing Revlon.

During mating season, the males - their bellies turning bright red with desire - swim up and down and around the females in a choose-me dance.

The Laurel Dace feeds on insects - caddisflies, mayflies, stoneflies, damselflies - and spawns multiple times each spring, laying dozens of eggs in the hidden spaces under and between rocks at the bottom of creek beds and streams.

It is also perilously close to extinction.

Its numbers so low, you can count them by hand.

The Laurel Dace is considered one of the most critically endangered fish in the US.

Scientists estimate there are perhaps 800 Laurel Dace left on Earth.

They're found in only one place on the planet.

Walden's Ridge, Tennessee.

"This is the last stream on planet Earth where you can reliably find Laurel Dace," said Dr. Bernie Kuhajda, aquatic conservation biologist with the Tennessee Aquarium.

We are standing in Bumbee Creek on Walden's Ridge, above Spring City, Tenn., at the end of a series of long roads - asphalt, gravel, dirt, rocks, ruts - on private land with a locked gate.

With us: Bernie and his team of scientists from the Tennessee Aquarium's Conservation Institute (TNACI).

They're in a race against time and human behavior to save the Laurel Dace from extinction.

There in Bumbee Creek, they toss seine nets into the knee-deep water, looking - hope, fear, all mixed together - for the small fish.

They find one.

"A female!" Bernie declares.

The fish is already small; its vulnerability makes it seem even smaller. The moment is surreal and dizzying with both exhilaration and grief, witnessing a creature whose population is so limited, the loss of even one is noted as tragic.

"Isn't she beautiful?" Bernie says.

Once upon a time, the Laurel Dace flourished in nine nearby streams. In the 90s, Bernie remembers driving by Soddy Creek, hopping out with a seine net and catching them hand-over-fist.

Now?

"They are completely gone," he said.

The Laurel Dace is threatened by several forces, from invasive species like bass and sunfish to haphazard land management practices that flood its habitat. Most of the threat can be summed up in one word:

"Sedimentation," Bernie said.

Sedimentation ruins and chokes out the Laurel Dace habitat.

Yet, sedimentation also impacts and damages human habitats - our economies, homes, businesses - as well.

Sedimentation is caused by humans and can be prevented by humans.

The Laurel Dace story portrays a boomerang effect: what befalls the Laurel Dace also befalls us.

Its story, parallel to ours.

"What the Laurel Dace is going through is exactly what we're going through," said Stephania Motes, Spring City's former city manager.

The Water Before Us is the first in a multi-part series examining the crucial role of larger landscapes within our region. In a special collaboration with Thrive Regional Partnership, Food as a Verb is expanding our coverage with a question:

What is the health of the watersheds and forests in the background beyond our farms and fields?

And what are the opportunities before us for healing?

In the race to save the little Laurel Dace, a precious and rare truth is discovered.

When the fish thrives, so do we.

Decades ago in college, Bernie signed up for vertebrate zoology; the professor, an ichthyologist, took field trips to a stream near campus. Bernie had driven by the stream dozens of times, never giving it a second glance.

But that undergraduate day, as he waded into the stream, a whole new world opened up, this underwater kingdom hidden in plain sight.

"All this amazing diversity hidden under the surface of the water," he said.

"I got hooked."

Degree after degree, publication after publication, Bernie built his career on conservation and freshwater fish.

"Freshwater covers less than one percent of the world," he said, "but about half of all species of fish are freshwater."

Here in the Southeast, particularly where Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia converge, we have a particular treasure:

"We have an underwater rainforest right here in the South," he said. "We are a global hotspot for freshwater diversity."

Thus, joy.

And vulnerability.

Within this rainforest-hotspot, there is tremendous interconnectivity. What happens in our fields impacts our streams, our towns, even - via the cavernous ground under our feet - our drinking water.

If you were to dye test water poured out in one field, you'd see it flowing to a thousand other places.

Everything affects everything. To understand all the interrelated parts, Bernie offers a Laurel Dace 101 crash course.

Remember its bulging eyes?

"They are sight feeders," Bernie said.

Standing on the Bumbee Creek rocks, he dips his boot in the water, and swirls it around. Immediately, mushrooms of dirt cloud the water.

"When the water looks like this, you're going to have trouble seeing aquatic insects to eat," he said.

Sedimentation fills in the spaces like chimney soot, dirtying clean gravel needed for spawning, clouding streams so fish can't find food and potentially decreasing oxygen levels.

Why the increased sedimentation?

Atop Walden's Ridge, hundreds of feet above Spring City, there are acres and acres of clear-cut.

In its natural state, the land boasts a built-in ability to absorb and contain rainfall, even torrential, like a natural buffer, so downstream watersheds aren't overwhelmed.

When practiced improperly, clear-cutting rips out the land's natural resiliency to hold water; when it rains, the land - stripped of its buffering ability - becomes like a race track, as rainfall floods into lower elevations.

This is why cities, historically, are more flood-prone than rural; all the impervious surfaces - parking lots, roads, asphalt - can't hold water, so runoff becomes fast and furious.

Clear-cutting replicates the urban in the rural. All the natural habitat is flattened, becoming a superhighway for rainwater runoff.

Logging roads must be cut; their ruts creating even more superhighways for overflow rainfall to rush into lower elevations.

Like Bumbee Creek.

And Spring City.

In the winter of 2019, the Piney River flooded its banks, causing massive destruction to Spring City businesses and families.

"It flooded roughly five city blocks in about five to 10 minutes," said Stephania Motes. (She's the former city manager; her two contributed photos follow.)

Downtown businesses took years to recover; some never did.

It was a wake-up call. In 2022, Spring City joined Thrive Regional Partnership's pilot Resilient Communities program, particularly for one reason:

"Flood mitigation," said Stephania.

Thrive and Spring City leaders hosted town halls and meetings around two central questions:

What is causing our flooding? Where are the solutions?

In one Resilient Communities meeting, Joel Houser with Open Space Institute mentioned the Laurel Dace: the rare, endangered fish only found nearby.

Stephania and former mayor Woody Evans stopped, with turned heads: say that again.

"We'd never heard of this before," she said.

The precious connection was made: that little fish is suffering in similar ways as Spring City residents.

"The sediment causing issues in the Laurel Dace's natural habitat was also causing flooding issues here," Stephania said.

Here, the Laurel Dace story becomes a beautiful postcard sent from rural Tennessee to the world: here's what possible when we work together.

Spring City suffered from flooding.

And the Laurel Dace suffered from over-sedimentation in its streams.

Both events are tied together.

Addressing one means addressing the other.

In doing so, something beautiful forms.

Community.

The Resilient Community process allowed neighbors, city leaders, land managers and business owners to meet together in conversation framed around solutions, not confrontation.

Stephania remembers land managers and business owners eager to learn about best practices.

"They actually wanted to start meeting with us," she said. "It really did open up a lot of doors."

Plus, Spring City leaders also saw opportunity.

"How special is it to find something in your own backyard that's nowhere else in the world?" she said.

Spring City began to embrace the Laurel Dace, which became the town's official fish. City leaders proclaimed May 17, 2025, as Laurel Dace Day. A downtown party, farmers' market, a 5k with more than 150 runners from as far away as Minneapolis and Washington State.

"We had runners from 36 different cities here," she said.

The embrace of the Laurel Dace has begun to transform Spring City: the tiniest, most vulnerable fish now linked to a city's identity.

"People's actions have consequences," Stephania said. "It may not be immediately in their backyard, but it does have consequences elsewhere."

Then, more help, more community.

In 2022, National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) partnered with the Aquarium on a multi-year project called Ridges to Rivers Regional Conservation Partnership Program.

The Ridges to Rivers project directly helps with on-ground training and financial support for regional farmers and land managers interested in shifting towards more regenerative or sustainable practices.

Clear-cutting will continue - wood, a renewable resource, will remain in demand - but best practices can reduce run-off damage downstream.

Local land managers are beginning to plant native grasslands post-cut, for example.

Farmers steeped in conventional practices often graze cattle near - and even into - streams and waterways, which reduces and even eliminates any riparian buffer between fields and waterways.

This leads to flooding which leads to sedimentation.

The shift? Rotational grazing and a fenced-off barrier between fields and waterways, which reduce run-off and downstream sedimentation.

Crop farmers who cover their rows with plastic for weed suppression often create super-waterslide conditions; when it rains, the water races over the plastic, often carrying pesticidal residue, downstream.

Sedimentation? Yes. Flooding? Yes.

The shift: planting live mulches and cover crops between rows reduces run-off, thus reducing sedimentation and flooding.

Yet, scientists and conservationists harbor one secret thought:

Will it be enough?

In 2024, the Laurel Dace faced an extinction-level event: the summer drought.

That summer, Bernie and his team went to check on the fish. Hiking through Bumbee Creek, they found: the water in the creek had nearly vanished.

"Bone dry," said Bernie.

The Laurel Dace were nearly all gone.

*******

TO Smith doesn't mince words. The former chief for Montana's Fish, Wildlife and Parks who also led conservation efforts in Texas, California and with Trout Unlimited - says two things about as plainly as possibly.

First: we live in a gem of a place.

"The lower Appalachia area around Chattanooga down towards Huntsville is the most biologically diverse area in North America," he said.

Second?

It's in dire trouble.

Particularly, our watersheds.

"Water is the biggest issue we have. Water and the sheer development. Development is fracturing the landscape and our water quality is under threat," he said.

"Water is the issue. Food comes after water. How are you going to do regenerative farming when you have a jacked-up watershed?"

Today, TO is the Director of Conservation for Southeastern Cave Conservancy and is quite adept at describing the cave wonderland underneath our feet: a porous geology of dissolving limestone that's best pictured not as solid rock, but a cavernous, Swiss Cheese underground.

"This is what is so special about where we live," he said. "It's karst."

This geological reality - a karst reality - affects everything downstream, including our drinking water.

In some places - Florida, California - rain falls and seeps into the ground, which holds, percolates and filters the water.

Not here.

"Like capillaries, like veins," TO said. "This whole area is like Sponge Bob Squarepants. That's what's under our feet.

"There's millions and millions and millions of tubes that range in size from the size of your hair up to as large as Mammoth Caverns. And they're everywhere."

When it rains, water seeps into those millions of hair-to-mammoth-sized highways, all bound for our watersheds.

Pour something on the ground, it's coming out in our water.

"It's on the A-Train," said TO. "It's going to run through a cave and under your feet and out into a spring and into the Tennessee River on its way to your drinking supply."

The Laurel Dace-Spring City tale is a looking glass into the larger story.

Spring City's embrace of the Laurel Dace is a microcosm for how communities and conservation can work together - trout streams in the West, forests in the Northeast - to solve intimately local problems.

TO spoke about Thrive and the quest for regional partnerships.

"If they are strategic about finding common threads, they can build a fabric through which a team of horses can solve some major problems," he said.

Less helpful practices are swapped for better ones.

Tiny fish benefit.

Farms benefit.

Downtowns and neighborhoods benefit.

Everything affects everything, and our actions have consequences. When the ecological truth of this - what goes into the ground there affects us here - becomes a political and cultural truth, things will shift.

Until then?

"It's like watching a horrible, horrible car accident and you can't do anything about it," said TO.

"You want to save those people. Stop the car! Don't turn left! You can see what can be done to prevent it, but it's up to them, not you."

Ten years ago, TNACI scientists went to Cupp Creek, also on Walden's Ridge, where Laurel Dace were known to be present.

With electroshock backpacks, they surveyed the water. They, too, were shocked.

"We counted 200 sunfishes and bass and we only found a single Laurel Dace," said Bernie. Three years later, the sunfish and bass population had tripled.

And the Laurel Dace were gone in Cupp Creek.

Invasive, the sunfish and bass escape from landowner ponds during flooding events, somehow making their way to streams and creeks, where vulnerable Laurel Dace have no defense.

"They have literally eaten all the minnows in Cupp Creek," said Bernie. "There are none left."

Then, last summer's drought.

TNACI scientists raced up to Walden's Ridge to search for Laurel Dace.

They found a few pockets, the scantest of puddles, raccoon tracks nearby. There, they found Laurel Dace huddling for survival.

In a moment of Noah's Ark urgency, they began scooping up and safeguarding the remaining Laurel Dace, transporting them back to TNACI's campus at The Baylor School.

They rescued 299 Laurel Dace.

One died during transport, leaving 298.

At TNACI, they began a heroic attempt at keeping a single species of fish preserved, alive and future-forward.

They filled tank after tank, with back-up generators and close-eye attention.

"We had all the Laurel Dace in the world here," said Bernie.

School kids visited, wrote notes.

Earlier this summer, Noah's Ark got bigger.

The Laurel Dace began spawning in TNACI tanks.

Now, baby Laurel Dace - the size of a grain of rice - number around 200 more.

Best estimate for all the living Laurel Dace?

"My best guess?" Bernie said. "Probably 800 to 900."

They've already released some back into Bumbee Creek. Days ago, they returned - hope, fear all mixed together - to survey their numbers.

They found one.

Then, another.

There were multiple juvenile Laurel Dace.

They'd spawned.

TNACI will always keep some Laurel Dace in its tanks, an Ark-ian insurance plan against a world that seems to tilt one way or the other:

Will we adopt new practices that protect and strengthen our communities, watersheds and natural habitats?

Will this tiny fish, facing peril at every turn, survive?

"Yes," Bernie said. "I am an eternal optimist. You have to be if your whole career is working with endangered species."

Behind him, swimming in tanks with back-up generators, hundreds of Laurel Dace, yellow running across their fins and midline, as if dipped in gold.

As if dipped in hope.

"Word will spread," he said. "I think we will turn it around."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.

For more information:

- Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (TNACI) "furthers the Aquarium’s impact by conducting scientific studies, restoring our region’s natural ecosystems and educating members of the public to take conservation action."

- Thrive Regional Partnership serves as a framework, connecting people to place in a wide network of relationships to inspire responsible growth in northeast Alabama, northwest Georgia and southeast Tennessee.

- Thrive's Natural Treasures Alliance is a collective of organizations working to accelerate landscape conservation to ensure a place that lasts for future generations.

- Southeastern Cave Conservancy is the world's largest land conservancy solely dedicated to protecting caves.