Howling in Marion County's National Park

Appalachian Conservation Institute is larger than some state parks.

Food as a verb thanks

for sponsoring this series

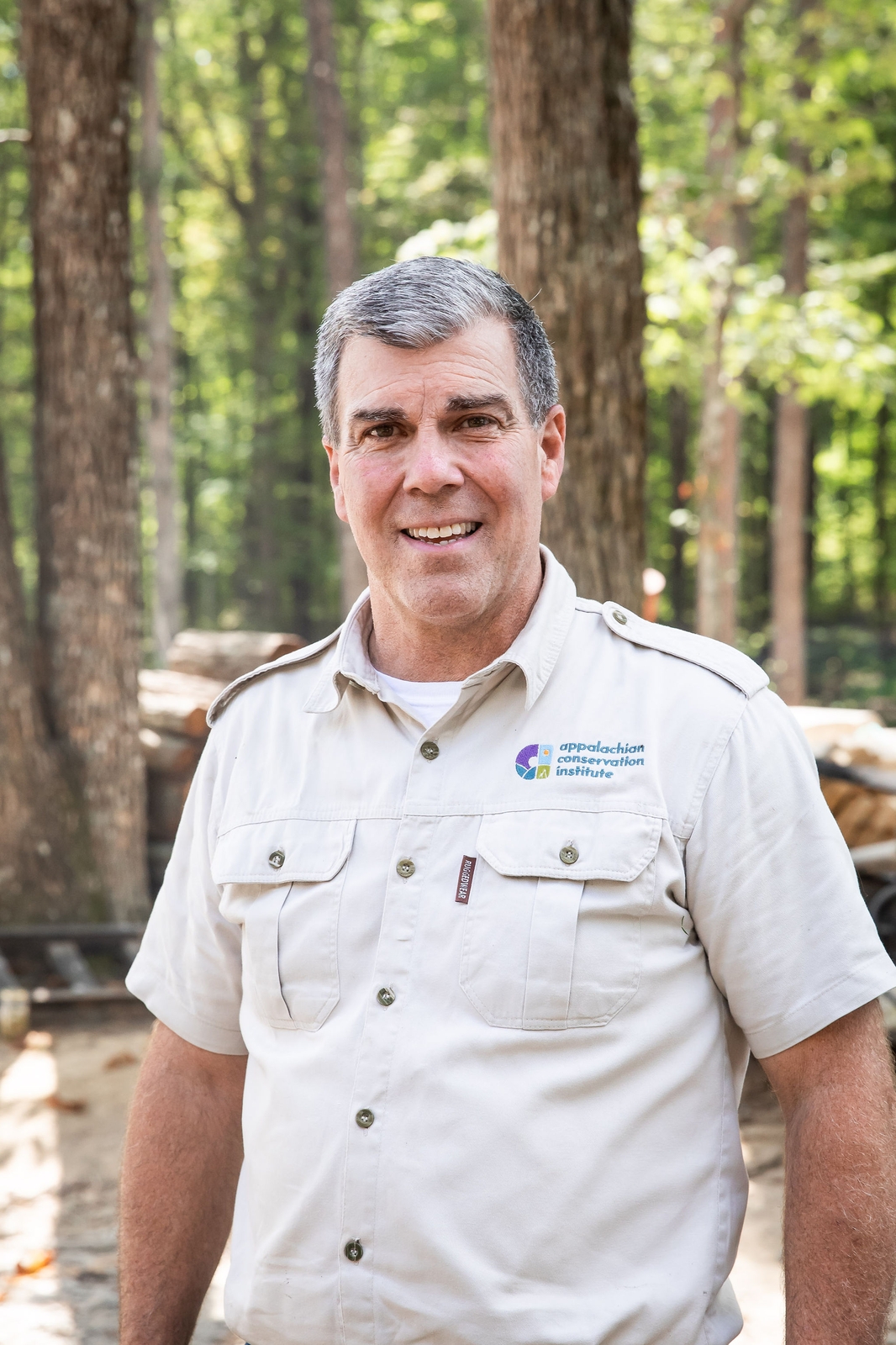

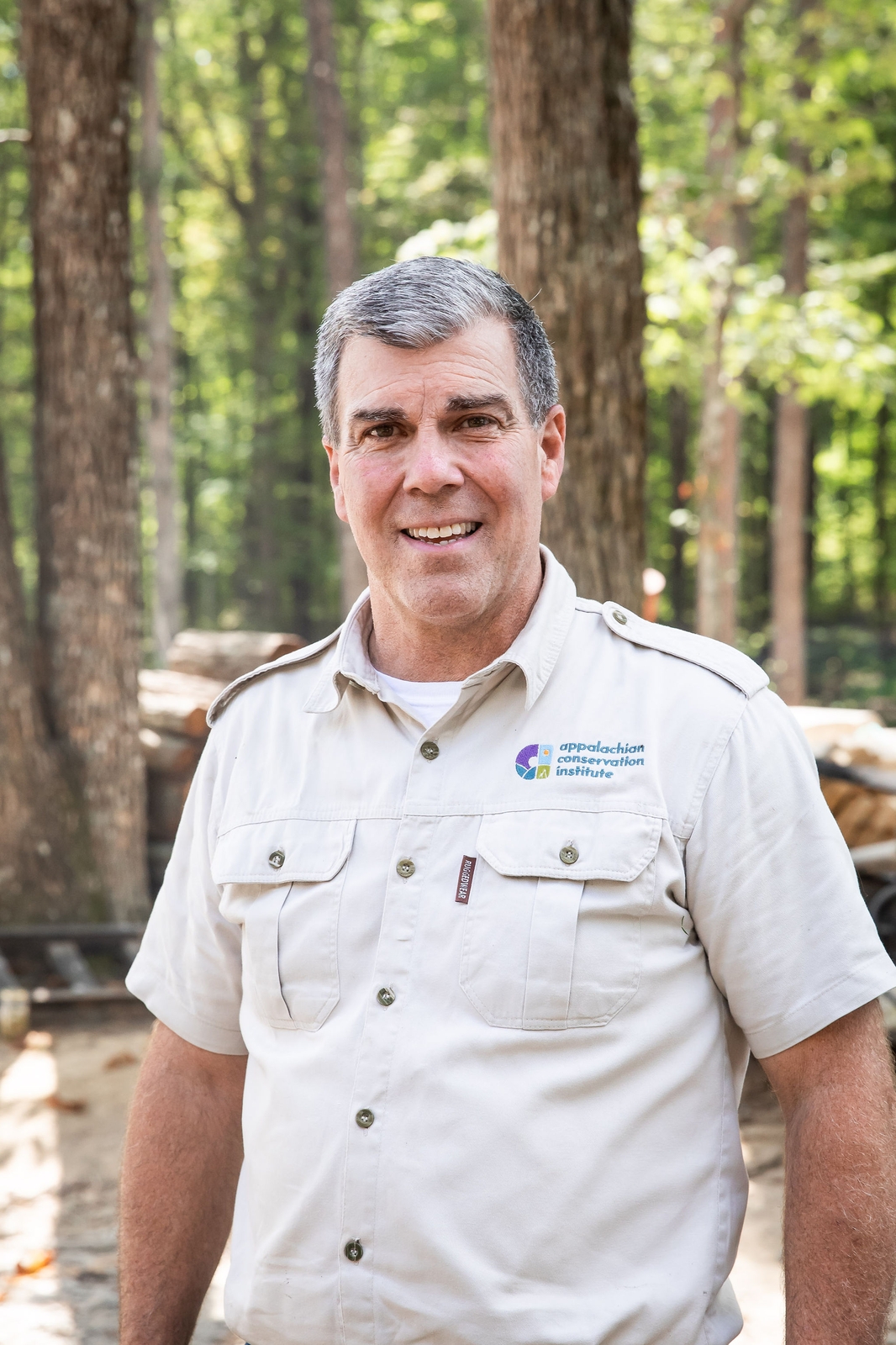

Before he began howling at coyotes or describing the smell of a woodpecker — "musty, mushroomy," he says — Rick Huffines, the veteran conservationist, stopped his ATV about 30 yards from where we were headed.

"What you're about to experience ..." he said, before pausing, as if unable to find the right words.

We were in the middle of 11,000 acres of Marion County wilderness, ATV-riding along with Rick past locked gates, down bumpy miles of roads and another mile of wooded trail.

That's when he hit the brakes.

He wanted us to see it first, like a docent who opens the museum after-hours and lets you walk through in silence.

"I'm going to give you a second by yourselves," he said.

Then, he tried again to find the words, to prep us.

"You're about to see this vastness," he said. "You're about to experience it."

We begin walking. The forest, once thick with trees, opens up. You have that feeling of walking upon something rare, uncommon, holy, like a midwife or knight or astronaut.

The dirt trail turns into more rock underfoot, you see the first peeks of a bluff.

There's the growing sense that we are about to ... walk upon ...

The edge of the world.

The silence is enormous and enveloping. In every direction: vastness, wilderness.

No roads, no sounds other than the wind and trees creaking, no homes, no human footprint. Inside, the tumblers turn; this view unlocks a head-to-toe feeling — Rick would call it a "blood memory" — of something primal or ancient or sacred.

We are the smallest possible versions of ourselves while also feeling equally and incredibly expansive.

Good Lord, have mercy, I kept saying.

After a few moments, Rick and Quentin Miller, his right-hand-man at the Marion County Louvre, walk up.

"Welcome to the middle of nowhere," Rick said. "Just take it in, real quiet."

The middle of nowhere is actually part of a boldly generous new nonprofit called the Appalachian Conservation Institute, or ACI.

Here in Marion County, ACI has protected more than 11,000 acres of land with a different model of conservation.

To understand, Rick and Quentin took us first to this view.

Their point? They want to share it. Conservation isn't only about protection.

After all, we're all drawn to this. All of us.

"It's one of the only few spots you can look north, south, east and west and there are no signs of houses or roads," Rick said.

The view funnels down into the Little Sequatchie River.

We are gazing at land with 72 counted cave openings that contain gray and tricolor bats and stalagmites and crawfish without eyes or pigment and human footprints dated thousands of years ago.

So, how do you protect it all without walling it off?

Many of you know Rick from his years at The River Gorge Trust, where he became the embodiment of local conservation efforts.

In 2023, he retired from the Trust, only to enter a swan song after bumping shoulders with a couple from Colorado.

I'm buying up land in Marion County, the Colorado man told Rick at a party.

What are you going to do with it?

I"m going to preserve it, protect it, the man said.

And I need your help.

They talked. Rick listened. 11,000 acres? Say that again?

"They wanted to turn this into a national park," Rick remembers, "but they didn't want the government running it."

In 2024, Rick said yes, becoming ACI's executive director.

The first few months on the job? Rick is old-school, sort of a tracker-poet; for the first few months, all he did was walk the land, get lost, listen, touch things.

"Listening, looking, smelling, touching," he said. "I want to connect to the land and be connected to it. It helps me understand what the land needs.

"Feeling the land beneath my feet.

"I feel like it needed to heal."

Then, Quentin Miller joined the team as associate director.

"You start thinking about how big 11,000 acres is," Quentin said. "It's bigger than some state parks."

ACI frames its mission around both protection and invitation. Quentin and Rick want you, too, experiencing this national-park-that-isn't in Marion County.

"Where do you get to go to do something like that? This is your backyard," Quentin said. "This is your home."

Conservation will look a little differently here, they said. The goal is not to keep people out, but to find ways to create balance between the needs of the land and the needs of a recreating population in Marion, Hamilton and surrounding counties.

ACI covers more acreage than many Tennessee state parks. It may never become a national park, but it sure can feel like one.

They have managed hunts, offering food sovereignty. Off-roading trails. Hiking, mountain biking, horseback riding, all offered through a free permiting system.

Yet, there's a balance, a see-saw between access and protection. There are 40 endangered and rare species here, one of which is found in fewer than five places on the planet.

"A vision of protected land thriving biologically," Rick said. "Land protection. Land restoration. Scientific exploration. "

He starts up the ATV. We're headed deeper into the forest.

Had we come here six months prior, the land would be thick with trees; you could stand 30 yards away and not be seen.

Now?

We are looking at a rare bog.

"A pine oak savannah," Rick said.

"It is one of the most rare microhabitats on the Cumberland Plateau," Quentin said. "Orchids, insects, amphibians, water reptiles, plants. There was no vegetation in that bog. Now look at it, six months later."

ACI incorporated a series of prescribed burns to reawaken the native grasses and fire tolerant species.

"Trees growing out here with deer rub on them, with frogs, salamanders and snakes. All the life in here. You see animals pawing and getting minerals," said Rick.

We rumble back up another trail to the sort of de facto headquarters, where Billy Nunley and his son Briley are working on a building.

They'd been on this land their whole lives, long before ACI arrived.

"We had a sawmill up here and around 300 head of hogs out here," he said. "We just camped and sawed wood."

In a way, the Nunleys are Marion County; ACI works to honor its Marion County roots first and foremost, protecting the community that's tied to this land.

"This is what we always wanted it to be," Billy said.

What's it mean to be part of this work?

"Everything," he said.

The ATV tour continues. We reach the highest point of the land, with multiple antennae pointing in all different directions.

Every 14 seconds, they pick-up frequencies within five to 15 kilometers. They're tracking for migratory banded birds.

"We know where that bird was originally tagged and where it came from," Rick said.

We load back into the ATV, passing a gun range and through another gate.

That's when I ask him the 11,000-acre question:

Rick, how do you define conservation?

He stands on the brake. The ATV grinds to a stop. It was the moment he'd been waiting for.

Rick pulls out a sheet of paper from his shirt pocket. Hand-written, folded two, three times. He's been contemplating this very question for years, and the other night, at home, an answer arrived.

So, he wrote it down.

"Conservation is a multitude of things," he began reading. "It is not just one thing.

"Conservation is the protection and preservation and management of natural environments. And the ecological communities that inhabit them."

Owning the land allows ACI "to protect it and preserve it and manage it and restore it.

"If all I do is protect development rights, I haven't done conservation holistically."

He's not picking a fight among conservationists. ("I don't want divisiveness. I'm so sick of it right now.")

"We connect to the land. We listen to the land. We let the birds tell us what they need. We let the forest tell us what it needs," he said.

Earlier that day, when we stood on the bluff at the edge of the world, Rick tiptoed out to the very edge, and said something we'll never forget.

What's this land taught you, Rick?

Once again, the vastness of it all exceeds vocabulary.

"How do I put this into words?" he said. "I still don't know enough. That's what it's taught me."

Then, he did something we'll never forget.

He began howling.

Howling, really howling, the primal, barbaric yeolp of Whitman.

"Give me about 30 seconds," he said.

We waited in the vastness. Then, miles away, in the distance ... the howls answered back.

Packs of coyotes, in a call-and-response with Rick.

"That's my buddies. Those are my friends. Sometimes, three or four packs of them," he said.

The howling echoes, then grows dimmer, then silence.

Rick wants you to hear this, too. A call-and-response from the land to the rest of us. That's why ACI is here.

"To give people access to come to a place like this," he said.

"Come here. Hear it. See it. Smell it," he said. "Howl to the coyotes."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.

food as a verb thanks our sustaining partner:

food as a verb thanks our story sponsor:

Rising Fawn Gardens

Before he began howling at coyotes or describing the smell of a woodpecker — "musty, mushroomy," he says — Rick Huffines, the veteran conservationist, stopped his ATV about 30 yards from where we were headed.

"What you're about to experience ..." he said, before pausing, as if unable to find the right words.

We were in the middle of 11,000 acres of Marion County wilderness, ATV-riding along with Rick past locked gates, down bumpy miles of roads and another mile of wooded trail.

That's when he hit the brakes.

He wanted us to see it first, like a docent who opens the museum after-hours and lets you walk through in silence.

"I'm going to give you a second by yourselves," he said.

Then, he tried again to find the words, to prep us.

"You're about to see this vastness," he said. "You're about to experience it."

We begin walking. The forest, once thick with trees, opens up. You have that feeling of walking upon something rare, uncommon, holy, like a midwife or knight or astronaut.

The dirt trail turns into more rock underfoot, you see the first peeks of a bluff.

There's the growing sense that we are about to ... walk upon ...

The edge of the world.

The silence is enormous and enveloping. In every direction: vastness, wilderness.

No roads, no sounds other than the wind and trees creaking, no homes, no human footprint. Inside, the tumblers turn; this view unlocks a head-to-toe feeling — Rick would call it a "blood memory" — of something primal or ancient or sacred.

We are the smallest possible versions of ourselves while also feeling equally and incredibly expansive.

Good Lord, have mercy, I kept saying.

After a few moments, Rick and Quentin Miller, his right-hand-man at the Marion County Louvre, walk up.

"Welcome to the middle of nowhere," Rick said. "Just take it in, real quiet."

The middle of nowhere is actually part of a boldly generous new nonprofit called the Appalachian Conservation Institute, or ACI.

Here in Marion County, ACI has protected more than 11,000 acres of land with a different model of conservation.

To understand, Rick and Quentin took us first to this view.

Their point? They want to share it. Conservation isn't only about protection.

After all, we're all drawn to this. All of us.

"It's one of the only few spots you can look north, south, east and west and there are no signs of houses or roads," Rick said.

The view funnels down into the Little Sequatchie River.

We are gazing at land with 72 counted cave openings that contain gray and tricolor bats and stalagmites and crawfish without eyes or pigment and human footprints dated thousands of years ago.

So, how do you protect it all without walling it off?

Many of you know Rick from his years at The River Gorge Trust, where he became the embodiment of local conservation efforts.

In 2023, he retired from the Trust, only to enter a swan song after bumping shoulders with a couple from Colorado.

I'm buying up land in Marion County, the Colorado man told Rick at a party.

What are you going to do with it?

I"m going to preserve it, protect it, the man said.

And I need your help.

They talked. Rick listened. 11,000 acres? Say that again?

"They wanted to turn this into a national park," Rick remembers, "but they didn't want the government running it."

In 2024, Rick said yes, becoming ACI's executive director.

The first few months on the job? Rick is old-school, sort of a tracker-poet; for the first few months, all he did was walk the land, get lost, listen, touch things.

"Listening, looking, smelling, touching," he said. "I want to connect to the land and be connected to it. It helps me understand what the land needs.

"Feeling the land beneath my feet.

"I feel like it needed to heal."

Then, Quentin Miller joined the team as associate director.

"You start thinking about how big 11,000 acres is," Quentin said. "It's bigger than some state parks."

ACI frames its mission around both protection and invitation. Quentin and Rick want you, too, experiencing this national-park-that-isn't in Marion County.

"Where do you get to go to do something like that? This is your backyard," Quentin said. "This is your home."

Conservation will look a little differently here, they said. The goal is not to keep people out, but to find ways to create balance between the needs of the land and the needs of a recreating population in Marion, Hamilton and surrounding counties.

ACI covers more acreage than many Tennessee state parks. It may never become a national park, but it sure can feel like one.

They have managed hunts, offering food sovereignty. Off-roading trails. Hiking, mountain biking, horseback riding, all offered through a free permiting system.

Yet, there's a balance, a see-saw between access and protection. There are 40 endangered and rare species here, one of which is found in fewer than five places on the planet.

"A vision of protected land thriving biologically," Rick said. "Land protection. Land restoration. Scientific exploration. "

He starts up the ATV. We're headed deeper into the forest.

Had we come here six months prior, the land would be thick with trees; you could stand 30 yards away and not be seen.

Now?

We are looking at a rare bog.

"A pine oak savannah," Rick said.

"It is one of the most rare microhabitats on the Cumberland Plateau," Quentin said. "Orchids, insects, amphibians, water reptiles, plants. There was no vegetation in that bog. Now look at it, six months later."

ACI incorporated a series of prescribed burns to reawaken the native grasses and fire tolerant species.

"Trees growing out here with deer rub on them, with frogs, salamanders and snakes. All the life in here. You see animals pawing and getting minerals," said Rick.

We rumble back up another trail to the sort of de facto headquarters, where Billy Nunley and his son Briley are working on a building.

They'd been on this land their whole lives, long before ACI arrived.

"We had a sawmill up here and around 300 head of hogs out here," he said. "We just camped and sawed wood."

In a way, the Nunleys are Marion County; ACI works to honor its Marion County roots first and foremost, protecting the community that's tied to this land.

"This is what we always wanted it to be," Billy said.

What's it mean to be part of this work?

"Everything," he said.

The ATV tour continues. We reach the highest point of the land, with multiple antennae pointing in all different directions.

Every 14 seconds, they pick-up frequencies within five to 15 kilometers. They're tracking for migratory banded birds.

"We know where that bird was originally tagged and where it came from," Rick said.

We load back into the ATV, passing a gun range and through another gate.

That's when I ask him the 11,000-acre question:

Rick, how do you define conservation?

He stands on the brake. The ATV grinds to a stop. It was the moment he'd been waiting for.

Rick pulls out a sheet of paper from his shirt pocket. Hand-written, folded two, three times. He's been contemplating this very question for years, and the other night, at home, an answer arrived.

So, he wrote it down.

"Conservation is a multitude of things," he began reading. "It is not just one thing.

"Conservation is the protection and preservation and management of natural environments. And the ecological communities that inhabit them."

Owning the land allows ACI "to protect it and preserve it and manage it and restore it.

"If all I do is protect development rights, I haven't done conservation holistically."

He's not picking a fight among conservationists. ("I don't want divisiveness. I'm so sick of it right now.")

"We connect to the land. We listen to the land. We let the birds tell us what they need. We let the forest tell us what it needs," he said.

Earlier that day, when we stood on the bluff at the edge of the world, Rick tiptoed out to the very edge, and said something we'll never forget.

What's this land taught you, Rick?

Once again, the vastness of it all exceeds vocabulary.

"How do I put this into words?" he said. "I still don't know enough. That's what it's taught me."

Then, he did something we'll never forget.

He began howling.

Howling, really howling, the primal, barbaric yeolp of Whitman.

"Give me about 30 seconds," he said.

We waited in the vastness. Then, miles away, in the distance ... the howls answered back.

Packs of coyotes, in a call-and-response with Rick.

"That's my buddies. Those are my friends. Sometimes, three or four packs of them," he said.

The howling echoes, then grows dimmer, then silence.

Rick wants you to hear this, too. A call-and-response from the land to the rest of us. That's why ACI is here.

"To give people access to come to a place like this," he said.

"Come here. Hear it. See it. Smell it," he said. "Howl to the coyotes."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.