The Words Before Us: a Glossary for 2026

Nature. Wilderness. Development. Have they lost their meaning?

Food as a verb thanks

for sponsoring this series

This is the third in a multi-story series with Thrive Regional Partnership.

The Before Us story series examines our shared connection to the region's landscapes and spotlights the people preserving them for generations to come.

Two facts are occurring simultaneously in our region.

The first: we are busting at the seams. Over the last decade, Chattanooga has become one of the most moved-to cities in the US, according to multiple studies.

The second?

This region is one the most biodiverse places on God's green earth.

Until recently, these two truths could coexist in relative ease, like two passengers on roomy train.

Now, as the train becomes crowded, we are reminded of the old western sheriff's line: seems there's only room in this town for one of us.

We either change the ways we treat this land or our original corner of this natural world will be lost.

Species lost.

Farmland lost.

Character and identity lost.

This dynamic and tension will only increase. Consider all the questions we face in 2026:

- What's the future of McDonald Farm and Enterprise South?

- How will we responsibly respond to growing farmland loss?

- How will South Broad and the Riverfront expansion impact regional housing and traffic?

- What is the future of Plan Hamilton?

In times like these, we need clarity.

Over the winter, Food as a Verb spoke with regional experts, asking their definition on three words:

- Nature

- Preservation

- Planning

How do you define them? What's your experience? Why do they matter?

The ways we define and interpret these words give us common ground. Otherwise, we live in a Tower-of-Babel existence.

Without shared meaning, there is no common ground.

The act of defining these words become paramount, as it creates the common ground that becomes the social soil for solutions.

By creating a shared glossary, we are creating common ground.

Here's what our experts said.

- Shawanna Kendrick, founder of The H20 Life.

"Nature is home," she said.

When Shawanna was young, her cousins would drive down from Michigan to visit.

Stretching and unrolling out of the car, they hugged, then, as the adults began talking and unpacking, Shawanna and her young cousins looked at each other: do you want to go to the tree?

Beaming, they would sprint to the backyard.

"We would climb this huge tree," she said.

It was a dogwood, which felt huge to them as kids, rooted in the corner of her parent's backyard near Bonny Oaks.

"We'd hang out in this tree on a branch not really talking about anything important to adults but important to us, enjoying that space and that time," she said.

The experience imprinted on her in unforgettable ways. It was freedom.

"We enjoyed this space without restriction," she said. "We just climbed. And we climbed freely."

Over time, Shawanna buried that tree in her heart and consciousness.

She grew older.

Encountered a culture and society that say: girls can't climb trees, especially while wearing a dress.

"Somewhere along the way, I stopped being the girl who climbed the tree," she said. "And I started being what society said I needed to be."

Many years later, she'd traveled to China as part of RISE Chattanooga. The 2019 trip included a visit to the most beautiful garden in Wuxi, China.

"It was magical," she said.

In that Chinese garden, something woke up inside.

"I remember how at peace I felt. How comfortable and relaxed I was ... so far away from home in a foreign country I'd never been in before," she said.

"And yet I felt at home."

Somewhere inside, the branches of that childhood tree began to stir in the wind.

On the return flight, she whispered a recorded message to herself: I don't know what this is, but something is going to be different.

Returning home, she approached some friends and coworkers with a novel idea: let's go hiking.

Her first hike? Signal Point.

"We laughed and let our hair down," she said. "We experienced a part of the area we've never experienced before. Never seen up close. Never ventured out. Never explored.

"To see the gorge and to be at the falls and overlooks, to spend time disconnected from all the things, felt like home.

"That's when I realized I can have both. I can do both. I can enjoy both."

In 2021, after a career in broadcast media, community engagement and journalism, Shawanna launched The H20 Life, our region's only organization dedicated to inviting and guiding Black women into the outdoors.

(Contributed portrait by Chris Shaw, Final Flash Productions)

As she leads groups of Black women into the woods and waters, she witnesses a precious experience of women remembering something too long forgotten: how to let go.

"It is so beautiful," she said. "I've seen the weight they've been carrying gently lift. It's as if they're walking in the woods and as they walk and with each step they take, they're shedding a piece of that weight, a part of that weight and leaving it on the trail."

This, for Shawanna, is the calling card of nature.

It feels like home.

"For me, home is always safe. A place of peace and comfort. I've always been at ease at home," she said.

"Nature is where I feel at peace. Where I feel solace. Where I feel really transparent.

"Nature is where I hear God."

From the backyard tree with her cousins to the garden in China to the first tentative hike at Signal Point, Shawanna knows nature by the call-and-response feelings it brings her.

"I'm free to be myself," she said, "without having to be in a performative role, without having to agree to disagree, without having to shrink, without having to nod when I am absolutely not in agreement.

"I'm free to be who I am authentically, openly and honestly when I'm in nature."

There, something rooted inside stirs and speaks.

"It is deep in my soul. It is in my heart and it is so clear. It's not a voice. It's not audible.

"But I know it's God.

"We're friends for life," she said. "Nature and I."

- TO Smith, director of conservation for Southeastern Cave Conservancy.

TO built his career in some of the nation's wildest places. The former head of Wildlife and Fisheries departments in multiple western states, TO also grew up on a Georgia farm.

To understand nature, TO asks folks one simple question:

"Do you have a houseplant?"

Yes. Many.

"Why?" he responded.

"Why does anyone have houseplants? You don't eat them. You don't really think of them as providing oxygen," he said.

But all around us, across the globe, humans have homes with houseplants.

There's a simple explanation.

"Humans need other living things," he said.

To define nature, TO uses the word "system." Natural systems are interwoven, interconnected relationships that humans, until recently, participated in.

"Nature is everything that is not somewhat created, structured architecturally by humans," he said.

"Look at the wilderness. That's nature. The air we breathe, the water we drink.

"Nature stems from the diversity of life."

Yes, there are places that touch nature, sort of like the borderlands. A backyard garden. The piers along the Riverwalk. Solitary trees in containers inside the mall.

Even houseplants.

They're natural ... but not nature.

"No," he said. "It's a living creature, it's natural, but it's completely encapsulated in a human construct and probably hybridized to do just that.

For eons, humans lived within this system: our paths were footpaths. Our clothes, tanned from hides. Our homes, built from trees, more hides.

"We were part of that tapestry," he said.

Now, we have migrated elsewhere, removed ourselves from an integrated and conscious part of that system and settled in an industrial + technological world that keeps nature at a distance.

"We separated ourselves from nature for the rudimentary reasons of safety and self preservation," he said.

Now, with separation comes great risk: our fundamental relationship with the natural world is severing.

"Humans have crossed a line," he said.

So, we subconsciously cling to a fabric from long ago, living with houseplants for no practical reason whatsoever ... other than the fact we feel better around living things.

Perhaps our connection to the wild is innate, always dormant. Thus, his Houseplant Theory.

Walk into any room. If there are houseplants, it just feels ... different.

"That's all you have to understand. Plants don't speak. We don't rub or pet those plants," he said.

"But a room with houseplants feels better."

Often, TO will walk into the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area — more than one million acres near the Continental Divide — and not return for two weeks.

Grizzly bears, streams, no houses, no phones, no jets flying over, no unnatural nosies.

"It's like houseplants on steroids," he said. "When I go to wilderness, I feel more in the moment, less in control, less safe.

"I like to go into the wilderness because it puts me squarely as a human that is part of the system and not as a human trying to separate from the system."

TO has friends who live in big US cities. For them, the wilderness is a small three-acre park or forest. For others, it's a potted ficus.

"The houseplant is the common thread," he said. "We all have that feeling."

He calls it consciousness.

"Consciousness of nature," he said.

- Bridgett Massengill, president and CEO of Thrive Regional Partnership.

She views development, planning and preservation as tied together.

"I see them all intermingled," she said.

"They have to go hand in hand. You literally can't do one without the other. If you try, you're going to fail."

Since 2012, Thrive has transcended boundaries to nurture relationships among multiple stakeholders — public, private, nonprofit, small and large — for whom community is worth defining, envisioning and creating.

"I want our organization, our region, stakeholders and residents to be thinking about the quality of life here that they love," Bridgett said.

"The culture they love.

"The landscape they love."

Answering those questions, Bridgett says, invokes both development and preservation.

"Hand-in-hand," she said.

Preservation without development?

"No growth, no development. We look the same way we did in the 1700s."

And development without preservation?

"Self-interest instead of community-interest. Serving of self and only self," she said.

And self-interest has the power to destroy the places we love most.

"It's almost like we're in a war in the battle of our identity that we all love and cherish," she said. "That is truly the crux of this."

From her downtown office, she often looks out for a view that's signature Chattanooga.

"Downtown, Stringer's Ridge, I can see the aquarium and Walden's Ridge," she said.

(Contributed photo by Thrive Regional Partnership)

The skyline represents the intentionality when both preservation and development are held together.

"That's what preservation is," she said. "We have buildings and history and culture and an identity here. That's what we've got to preserve and develop in a way that retains that identity."

Bridgett said identity is rooted in three places:

Rooted in the natural.

Rooted in the built.

Rooted in the human culture story.

Find these three and you find the heartbeat of a community.

"The heartbeat is always going to be the strength of your community," she said.

Raze a strip mall. No one mourns. Tear down a mountainside? Bulldoze a historic bank building?

"When it hurts when it's gone, you know there's a heartbeat behind it," she said.

Thrive serves as the convener of community members and provider of resources and best practices, giving Bridgett a powerful symbol to consider.

"We need to be the thermostat and not the thermometer," she said.

Thermometers only measure what's happening. A thermostat can create the atmospherics and environment of a place.

She wants communities to function as thermostats, able to proclaim — with power — in the face of development without preservation: this is not the quality of life we want, this is not the preservation of who we are.

"We need to make sure we can create the conditions that keep us in the place we all love," she said.

"Decisions are beginning to erode the very fabric of the things that people love about our community. We don't want to love to death the things we love the most."

So, Thrive offers research-based best practices and resources and tools for decision-makers in our region. By strengthening relationships, Thrive steers us towards a future with greater bonds and understanding.

Plus, small towns often left out of decision-making now have a seat at the table. Or, even better?

"We want to offer a table to anyone who doesn't have one," she said.

There are a few facts occurring simultaneously in this region.

Development will continue in this region.

More and more people will move here.

More farmland and wild places will be lost.

Yet, it's possible for us to limit this loss with intentional and responsible planning based on community-interest.

We can preserve and protect the foundational aspects of our community and natural world that we love best.

"Those are the things we want to preserve," said Bridgett. "The integrity of this place we call home."

No one said it would be easy.

But it can happen.

In many places, it is happening.

Elected officials are trying to make ethical, wholesome decisions that benefit the communities they serve.

Business leaders, developers and farmers are staying true to the best practices they can, holding onto an ethical thread despite forces pulling them elsewhere.

That thread is always found in a social soil, a common ground, a shared understanding.

The words before us, like the thread, lead the way.

Sure, this work can feel like a mountain, the most difficult of journeys.

Then, you reach the top.

"What's on the other side of the mountain," Shawanna said, "is something more beautiful than we could ever imagine or thought we could be able to see."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.

This is the third in a multi-story series with Thrive Regional Partnership.

The Before Us story series examines our shared connection to the region's landscapes and spotlights the people preserving them for generations to come.

Two facts are occurring simultaneously in our region.

The first: we are busting at the seams. Over the last decade, Chattanooga has become one of the most moved-to cities in the US, according to multiple studies.

The second?

This region is one the most biodiverse places on God's green earth.

Until recently, these two truths could coexist in relative ease, like two passengers on roomy train.

Now, as the train becomes crowded, we are reminded of the old western sheriff's line: seems there's only room in this town for one of us.

We either change the ways we treat this land or our original corner of this natural world will be lost.

Species lost.

Farmland lost.

Character and identity lost.

This dynamic and tension will only increase. Consider all the questions we face in 2026:

- What's the future of McDonald Farm and Enterprise South?

- How will we responsibly respond to growing farmland loss?

- How will South Broad and the Riverfront expansion impact regional housing and traffic?

- What is the future of Plan Hamilton?

In times like these, we need clarity.

Over the winter, Food as a Verb spoke with regional experts, asking their definition on three words:

- Nature

- Preservation

- Planning

How do you define them? What's your experience? Why do they matter?

The ways we define and interpret these words give us common ground. Otherwise, we live in a Tower-of-Babel existence.

Without shared meaning, there is no common ground.

The act of defining these words become paramount, as it creates the common ground that becomes the social soil for solutions.

By creating a shared glossary, we are creating common ground.

Here's what our experts said.

- Shawanna Kendrick, founder of The H20 Life.

"Nature is home," she said.

When Shawanna was young, her cousins would drive down from Michigan to visit.

Stretching and unrolling out of the car, they hugged, then, as the adults began talking and unpacking, Shawanna and her young cousins looked at each other: do you want to go to the tree?

Beaming, they would sprint to the backyard.

"We would climb this huge tree," she said.

It was a dogwood, which felt huge to them as kids, rooted in the corner of her parent's backyard near Bonny Oaks.

"We'd hang out in this tree on a branch not really talking about anything important to adults but important to us, enjoying that space and that time," she said.

The experience imprinted on her in unforgettable ways. It was freedom.

"We enjoyed this space without restriction," she said. "We just climbed. And we climbed freely."

Over time, Shawanna buried that tree in her heart and consciousness.

She grew older.

Encountered a culture and society that say: girls can't climb trees, especially while wearing a dress.

"Somewhere along the way, I stopped being the girl who climbed the tree," she said. "And I started being what society said I needed to be."

Many years later, she'd traveled to China as part of RISE Chattanooga. The 2019 trip included a visit to the most beautiful garden in Wuxi, China.

"It was magical," she said.

In that Chinese garden, something woke up inside.

"I remember how at peace I felt. How comfortable and relaxed I was ... so far away from home in a foreign country I'd never been in before," she said.

"And yet I felt at home."

Somewhere inside, the branches of that childhood tree began to stir in the wind.

On the return flight, she whispered a recorded message to herself: I don't know what this is, but something is going to be different.

Returning home, she approached some friends and coworkers with a novel idea: let's go hiking.

Her first hike? Signal Point.

"We laughed and let our hair down," she said. "We experienced a part of the area we've never experienced before. Never seen up close. Never ventured out. Never explored.

"To see the gorge and to be at the falls and overlooks, to spend time disconnected from all the things, felt like home.

"That's when I realized I can have both. I can do both. I can enjoy both."

In 2021, after a career in broadcast media, community engagement and journalism, Shawanna launched The H20 Life, our region's only organization dedicated to inviting and guiding Black women into the outdoors.

(Contributed portrait by Chris Shaw, Final Flash Productions)

As she leads groups of Black women into the woods and waters, she witnesses a precious experience of women remembering something too long forgotten: how to let go.

"It is so beautiful," she said. "I've seen the weight they've been carrying gently lift. It's as if they're walking in the woods and as they walk and with each step they take, they're shedding a piece of that weight, a part of that weight and leaving it on the trail."

This, for Shawanna, is the calling card of nature.

It feels like home.

"For me, home is always safe. A place of peace and comfort. I've always been at ease at home," she said.

"Nature is where I feel at peace. Where I feel solace. Where I feel really transparent.

"Nature is where I hear God."

From the backyard tree with her cousins to the garden in China to the first tentative hike at Signal Point, Shawanna knows nature by the call-and-response feelings it brings her.

"I'm free to be myself," she said, "without having to be in a performative role, without having to agree to disagree, without having to shrink, without having to nod when I am absolutely not in agreement.

"I'm free to be who I am authentically, openly and honestly when I'm in nature."

There, something rooted inside stirs and speaks.

"It is deep in my soul. It is in my heart and it is so clear. It's not a voice. It's not audible.

"But I know it's God.

"We're friends for life," she said. "Nature and I."

- TO Smith, director of conservation for Southeastern Cave Conservancy.

TO built his career in some of the nation's wildest places. The former head of Wildlife and Fisheries departments in multiple western states, TO also grew up on a Georgia farm.

To understand nature, TO asks folks one simple question:

"Do you have a houseplant?"

Yes. Many.

"Why?" he responded.

"Why does anyone have houseplants? You don't eat them. You don't really think of them as providing oxygen," he said.

But all around us, across the globe, humans have homes with houseplants.

There's a simple explanation.

"Humans need other living things," he said.

To define nature, TO uses the word "system." Natural systems are interwoven, interconnected relationships that humans, until recently, participated in.

"Nature is everything that is not somewhat created, structured architecturally by humans," he said.

"Look at the wilderness. That's nature. The air we breathe, the water we drink.

"Nature stems from the diversity of life."

Yes, there are places that touch nature, sort of like the borderlands. A backyard garden. The piers along the Riverwalk. Solitary trees in containers inside the mall.

Even houseplants.

They're natural ... but not nature.

"No," he said. "It's a living creature, it's natural, but it's completely encapsulated in a human construct and probably hybridized to do just that.

For eons, humans lived within this system: our paths were footpaths. Our clothes, tanned from hides. Our homes, built from trees, more hides.

"We were part of that tapestry," he said.

Now, we have migrated elsewhere, removed ourselves from an integrated and conscious part of that system and settled in an industrial + technological world that keeps nature at a distance.

"We separated ourselves from nature for the rudimentary reasons of safety and self preservation," he said.

Now, with separation comes great risk: our fundamental relationship with the natural world is severing.

"Humans have crossed a line," he said.

So, we subconsciously cling to a fabric from long ago, living with houseplants for no practical reason whatsoever ... other than the fact we feel better around living things.

Perhaps our connection to the wild is innate, always dormant. Thus, his Houseplant Theory.

Walk into any room. If there are houseplants, it just feels ... different.

"That's all you have to understand. Plants don't speak. We don't rub or pet those plants," he said.

"But a room with houseplants feels better."

Often, TO will walk into the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area — more than one million acres near the Continental Divide — and not return for two weeks.

Grizzly bears, streams, no houses, no phones, no jets flying over, no unnatural nosies.

"It's like houseplants on steroids," he said. "When I go to wilderness, I feel more in the moment, less in control, less safe.

"I like to go into the wilderness because it puts me squarely as a human that is part of the system and not as a human trying to separate from the system."

TO has friends who live in big US cities. For them, the wilderness is a small three-acre park or forest. For others, it's a potted ficus.

"The houseplant is the common thread," he said. "We all have that feeling."

He calls it consciousness.

"Consciousness of nature," he said.

- Bridgett Massengill, president and CEO of Thrive Regional Partnership.

She views development, planning and preservation as tied together.

"I see them all intermingled," she said.

"They have to go hand in hand. You literally can't do one without the other. If you try, you're going to fail."

Since 2012, Thrive has transcended boundaries to nurture relationships among multiple stakeholders — public, private, nonprofit, small and large — for whom community is worth defining, envisioning and creating.

"I want our organization, our region, stakeholders and residents to be thinking about the quality of life here that they love," Bridgett said.

"The culture they love.

"The landscape they love."

Answering those questions, Bridgett says, invokes both development and preservation.

"Hand-in-hand," she said.

Preservation without development?

"No growth, no development. We look the same way we did in the 1700s."

And development without preservation?

"Self-interest instead of community-interest. Serving of self and only self," she said.

And self-interest has the power to destroy the places we love most.

"It's almost like we're in a war in the battle of our identity that we all love and cherish," she said. "That is truly the crux of this."

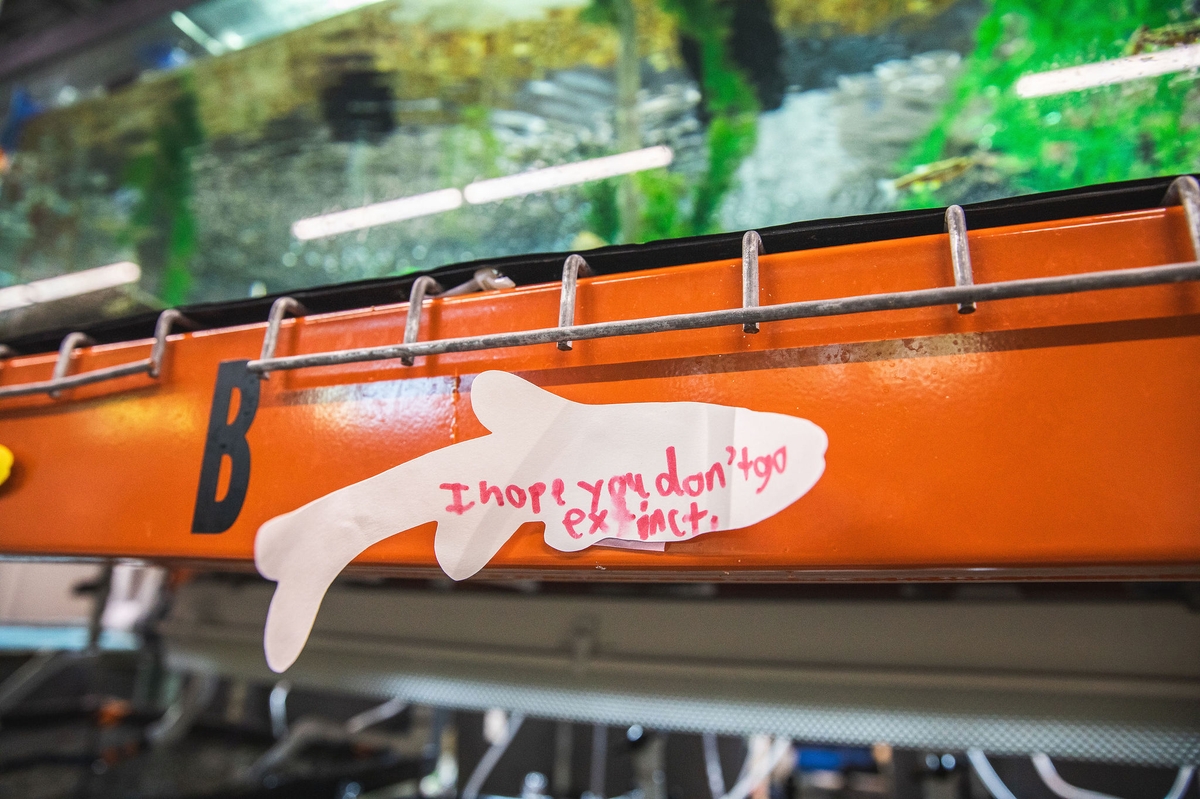

From her downtown office, she often looks out for a view that's signature Chattanooga.

"Downtown, Stringer's Ridge, I can see the aquarium and Walden's Ridge," she said.

(Contributed photo by Thrive Regional Partnership)

The skyline represents the intentionality when both preservation and development are held together.

"That's what preservation is," she said. "We have buildings and history and culture and an identity here. That's what we've got to preserve and develop in a way that retains that identity."

Bridgett said identity is rooted in three places:

Rooted in the natural.

Rooted in the built.

Rooted in the human culture story.

Find these three and you find the heartbeat of a community.

"The heartbeat is always going to be the strength of your community," she said.

Raze a strip mall. No one mourns. Tear down a mountainside? Bulldoze a historic bank building?

"When it hurts when it's gone, you know there's a heartbeat behind it," she said.

Thrive serves as the convener of community members and provider of resources and best practices, giving Bridgett a powerful symbol to consider.

"We need to be the thermostat and not the thermometer," she said.

Thermometers only measure what's happening. A thermostat can create the atmospherics and environment of a place.

She wants communities to function as thermostats, able to proclaim — with power — in the face of development without preservation: this is not the quality of life we want, this is not the preservation of who we are.

"We need to make sure we can create the conditions that keep us in the place we all love," she said.

"Decisions are beginning to erode the very fabric of the things that people love about our community. We don't want to love to death the things we love the most."

So, Thrive offers research-based best practices and resources and tools for decision-makers in our region. By strengthening relationships, Thrive steers us towards a future with greater bonds and understanding.

Plus, small towns often left out of decision-making now have a seat at the table. Or, even better?

"We want to offer a table to anyone who doesn't have one," she said.

There are a few facts occurring simultaneously in this region.

Development will continue in this region.

More and more people will move here.

More farmland and wild places will be lost.

Yet, it's possible for us to limit this loss with intentional and responsible planning based on community-interest.

We can preserve and protect the foundational aspects of our community and natural world that we love best.

"Those are the things we want to preserve," said Bridgett. "The integrity of this place we call home."

No one said it would be easy.

But it can happen.

In many places, it is happening.

Elected officials are trying to make ethical, wholesome decisions that benefit the communities they serve.

Business leaders, developers and farmers are staying true to the best practices they can, holding onto an ethical thread despite forces pulling them elsewhere.

That thread is always found in a social soil, a common ground, a shared understanding.

The words before us, like the thread, lead the way.

Sure, this work can feel like a mountain, the most difficult of journeys.

Then, you reach the top.

"What's on the other side of the mountain," Shawanna said, "is something more beautiful than we could ever imagine or thought we could be able to see."

Story ideas, questions, feedback? Interested in partnering with us? Email: david@foodasaverb.com

This story is 100% human generated; no AI chatbot was used in the creation of this content.